In anticipation of this month's total solar eclipse, here’s a rundown of what to know.

Solar eclipses are not all that rare—in fact, there are usually two to four occurring each year—but a total solar eclipse is definitely worth watching (safely, of course). Since so much of the Earth’s surface is covered by oceans, it’s pretty unique for humans to get to witness this in person. In anticipation of the upcoming 2024 total solar eclipse, here’s a quick guide about eclipses and how (or how much) they affect solar panels.

What is a solar eclipse?

A solar eclipse occurs when the Moon passes between the Sun and the Earth, therefore blocking out Sun’s light. When the Moon only blocks part of the Sun, it’s called a ‘partial solar eclipse.’ So, a total solar eclipse happens when the Moon fully covers the Sun, therefore casting a shadow over Earth as it rotates.

For any solar eclipse, there’s what scientists refer to as the ‘path of totality.’ As described in USA Today, ‘the path of totality is the area where people on Earth can see the moon completely cover the Sun as the moon’s shadow falls upon them.’

The last big solar eclipse was in 2017

The last solar eclipse occurred on August 21, 2017. According to Nasa, an estimated 215 million U.S. adults, which is 88% of U.S. adults, viewed the solar eclipse directly or online. They were able to witness the Moon partially covering the Sun’s light. For those in the ‘path of totality, the sky was dark and the Sun’s light could be seen radiating from behind the Moon. Many were able to see the Sun partially or fully covered by the Moon.

One differentiator between 2024’s upcoming eclipse and that of 2017 is the distance of the Moon from the Earth. The path of totality will be much wider in this upcoming eclipse than it was in 2017.

Nasa notes that in 2017, the path ranged from about 62 to 71 miles wide. On April 8th, the path over North America will range from 108 and 122 miles wide. The wider the path, the more areas the eclipse will impact.

A solar eclipse does affect solar panels, but not as much as you think

This year’s solar eclipse will hit a bit different, mostly because much more of the country relies on solar power than it did in 2017. Since a solar eclipse does temporarily block out the Sun’s light, there will be less sunlight available that day to generate solar power. According to CNET, the total loss of sunlight will only last for about four minutes in any one place. Still, four minutes is almost double that of the solar eclipse of 2017. Experts also note that the transition in and out of the eclipse can last up to a few hours in some areas.

The New York Times reports that while the solar eclipse could cause a sharp decrease in electricity production in certain parts of the country and theoretically leave tens of millions of Americans without power, hardly anyone will notice a sudden loss of energy. They go on to add that electric utility companies have already lined up alternative sources of energy including natural gas power plants and battery installations.

Texas will be among the states most affected

While 2017’s solar eclipse had California in the path of totality, Texas is in the spotlight–no pun intended–this time around. Cities like San Antonio, Dallas, and Austin are densely populated cities where many homeowners rely on solar power.

As reported on Business Insider, power will likely drop to around 14 gigawatts. For reference, 1 gigawatt can power 100 million LED bulbs and 2.469 Million Photovoltaic (PV) Panels (source: the Office of Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy).

How to prepare

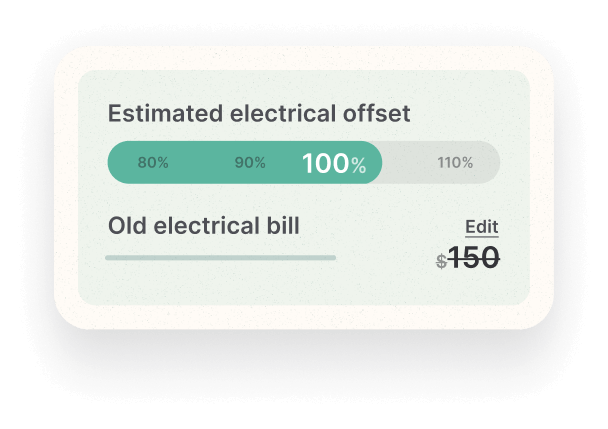

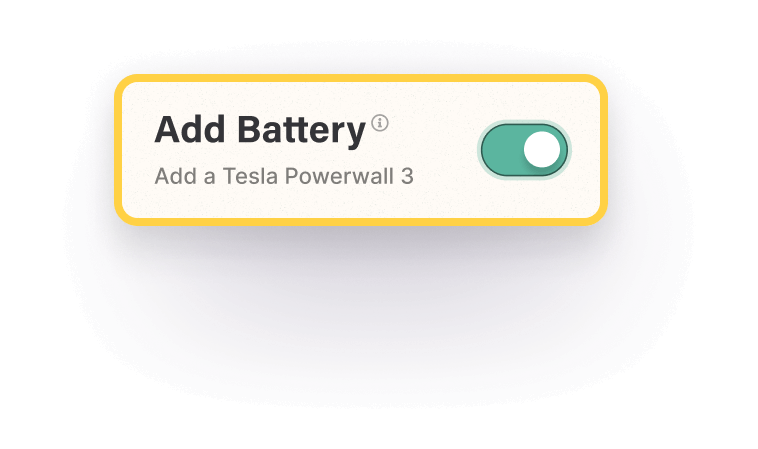

If you’re only affected by the solar eclipse to a small or moderate degree, we wouldn’t worry. For homeowners in Texas or other states within the path of totality, consider relying on your battery that day (of course, if you have one as part of your solar system).

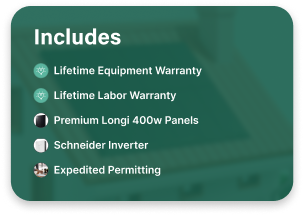

As we cover here, investing in a dedicated battery provides peace of mind during outages–and, in this case, eclipses–because you know you’re covered.

For those who do not have a dedicated battery but do benefit from net metering, consider using your stored up credits on April 8th so that your home isn’t affected by the dip in solar production.